Typography - Task 1 : Exercise 1 & 2

29/9/2023 - 5/11/2023 / (Week 1 - Week 5)

Aisya Diva Anwagodsa (0365505)

Typography / Bachelor of Design (Hons) in Creative Media

Typography

Task 1

JUMPLINK

- Square capitals were the written version that can be found in Roman monuments. These letterform have serifs to the finish of the main strokes.

- Rustic capitals a compressed version of square capitals. It took less time to write (the pen brush was held at an angle approximately 30°). However, rustic capitals were slightly harder to read due to their compressed nature.

- Roman cursive simplified for speed, the beginning of lowercase letterforms.

- Uncials, incorporated some aspects of the Roman cursive hand. The broad forms of uncials are more readable at small sizes than rustic capitals.

- Half-Uncials, a further formalization of the cursive hand.

- Charlemagne, the first unifier of Europe since the Romans, issued an edict in 789 to standardize all ecclesiastical texts. He entrusted this task to Alcuin of York, Abbot of St Martin of Tours. The monks rewrote the texts using both majuscules (uppercase), minuscule, capitalization and punctuation which set the standard for calligraphy for a century.

- Blackletter to Gutenberg's type, with the dissolution of Charlemagne's empire came regional variations upon Alcuin's script. In northern Europe, a condense strongly vertical letterform know as Blackletter or textura gained popularity. In the south, a rounder more open hand gained popularity, called 'rotunda'. The humanistic script in Italy is based on Alcuin's miniscule.

The text on the left are easier to read rather than the

right text that has been given letterspace, it reduce the readability of the

right text.

Tex: Formatting Text

Flush Left : this format most closely mirrors the asymmetrical experience of handwriting. Each line starts at the same point but ends wherever the last word on the lines ends. Spaces between words are consistent throughout the text, allowing the type to create an even gray value.

Centered : This format imposes symmetry upon the text, assigning equal value and weight to both ends of any line. It transform fields of text into shapes, thereby adding a pictorial quality to material that is non-pictorial by nature. Because centered type creates such a strong shape on the page, its important to amend line breaks so that the text does not appear too jagged.

Flush right : this format places emphasis on the end of a

line as opposed to its start. It can be

useful in situations (like captions) where the relationship between text and

image might be ambiguous without a strong orientation to the right.

Justified : Like centering, this format impose a symmetrical shape on the text. It is achieved by expanding or reducing spaces between words and, sometimes, between letters. The resulting openness of lines can occasionally produce 'rivers' of white space running vertically through the text. Careful attention to line breaks and hyphenation is required to amend this problem whenever possible.

Texture

Fig. 4.9 Different typefaces with different gray values

Type size : Text type should be large enough to be read

and easily at arms length-imagine yourself holding a book in your lap.

Leading : Text that is set too tightly encourages

vertical eye movement; a reader can easily loose his or her place. Type that is set too loosely creates striped

patterns that distract the reader from the material at hand.

Line Length : Appropriate leading for text is as much

a function of the line length as it is a question of type size and leading. Shorter lines require less leading; longer

lines more. A good rule of thumb is

to keep line length between 55-56 characters.

Extremely long or short lines lengths impairs reading.

Type Specimen Book

A type specimen book shows samples of typefaces in various different

sizes. Without printed pages showing

samples of typefaces at different sizes, no one can make a reasonable choice of

type. We can only determine choice on screen

when its final version is to read on screen.

A type specimen book (or e-book for screen) is to provide an accurate reference

for type, type size, type leading, type

line length etc.

Compositional requirement : Text

should create a field that can occupy a page or a screen. Think of your ideal text as having a middle

gray value (on the left, in the diagram below), not a series of stripes (as

seen of the one on the right).

There are several options for indicating paragraphs. In the first example, we see the ‘pilcrow’ (¶), a holdover from medieval manuscripts seldom use today

The picture displays a ‘line space’ (leading) between the paragraphs. Hence if the line space is 12pt, then the paragraph space is 12pt. This ensures cross-alignment across columns of text.

The example here displays the

standard indentation. Typically here the

indent is the same size of the line spacing or the same as the point size of your

text. Indentation is best when you use

justified.

The method of extended paragraphs below

creates unusually wide columns of text. Despite

these problems, there can be strong compositional or functional reasons for

choosing it.

Widows and Orphans

In traditional typesetting (the

kind that still endures among conscientious commercial publishers), there are

two unpardonable gaffes-widows and orphans.

Designers (specifically those that deal with large amounts of text in

websites or books on online magazines or printed magazines, news papers or

online journals) must take great care to avoid the occurrence of the above

mentioned.

A widow is a short line of type

left alone at the end of a column of text.

An orphan is a short line of type

left alone at the start of new column.

In justified text both widows and

orphans are considered serious gaffes. Flush

right and ragged left text is some what more forgiving towards widows, but only

a bit. Orphans remains

unpardonable.

The only solution to widows is to

rebreak your line endings through our your paragraph so that the last line of

any paragraph is not noticeably short.

Orphans, you might expect, require more care. Careful typographers make sure that no column of text starts with the last line of the preceding paragraph.

Highlighting Text

The following are some simple

examples of how to highlight text within a column of text. Different kinds of emphasis require different

kinds of contrast.

Color that can apply to highlighted

text are cyan, magenta, and black.

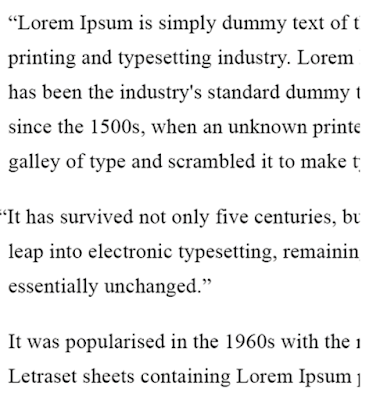

Quotation marks, like bullets, can

create a clear indent, breaking the left reading axis. Compare the indented quote at the top with

the extended quote at the bottom.

A prime is not a quote. The prime is an abbreviation for inches and

feet. Due to the limited number of keys

on a typewriter, they were substituted.

They were later known as ‘dumb quotes’.

Headline Within Text

There are many kinds of subdivisions within text of a chapters. In the following visuals these have been labelled (A, B, and C) according to the level of importance.

Em/en: Originally referring to the

width of an uppercase M, and em is now the distance equal to the size of the

typeface (an em in 48 points, for example).

An en is half the size of an em.

Most often used to describe em/en spaces and em/en dashes.

Finial: The rounded non-serif

terminal to a stroke.

Leg: Short stroke off the stem of

the letterform, either at the bottom of the stroke (L) or inclined downward (K,

R).

Ligature: The character formed by

the combination of two or more letterforms.

Link: The stroke that

connects the bowl and the loop of a lowercase G.

Loop: The loop created in the

descender of the lowercase G in some typefaces.

Uppercase: Capital letters, including certain accented vowels, the c cedilla and n tilde, and the a/e and o/e ligatures.

Uppercase Numerals: Also called

lining figures, these numerals are the same height as uppercase letters and are

all set to the same kerning width. They

are most successfully used with tabular material or in any situation that calls

for uppercase letters.

Lowercase Numerals: Also known as

old style figures or text figures, these numerals are set to x-height with

ascenders and descenders. They are best

used when ever you would use upper and lowercase letterforms. Lowercase numerals are far less common in

sans serif type-faces than in serif.

Italic: Most fonts today are

produced with a matching italic. Small

caps, however, are almost always only roman.

The forms in a italic refer back to fifteenth century Italian cursive

handwriting. Oblique are typically based

on the roman from of the typeface.

Punctuation, miscellaneous

characters although all fonts contain standard punctuation marks, miscellaneous

characters can change from typeface to typeface. It is important to be acquainted with all the

characters available in a typeface before you choose the appropriate type for job.

Ornaments Used as flourishes in

invitations or certificates. They

usually are provided as a font in a larger typeface family. Only a few traditional or classical typefaces

contain ornamental fonts as part of the entire typeface family (Adobe Caslon

Pro).

Roman the letterform is so

called because the uppercase forms are derived from inscriptions of Roman

monuments. A slightly lighter stroke in

roman is known as ‘Book’.

Italic named for fifteenth

century Italian handwriting on which the forms are based. Oblique conversely is based on roman form of

typeface.

Boldface characterized by

thick strokes. It is depended on the

relative stroke widths, it can be called semi bold, medium, black, extra bold,

or super. In some typefaces (notably

Bodoni), the boldest rendition of the typeface is referred to as ‘Poster’.

Light characterized by

lighter stroke than the roman form. Even

lighter strokes are called thin.

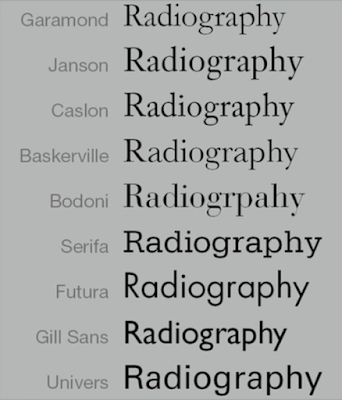

The 10 typefaces represent 500

years of type design. The men and women

who rendered them all sought to achieve two goals: easy readability and an

appropriate expression of contemporary aesthetics. These typefaces (and there are others) have

surpassed the latter goal. They have

remained in use for decades—in some cases, centuries—after they were first

designed, still considered successful expressions of how we think, how we read

and write, and how we print. As a

beginning typographer we should learn more about these ten faces carefully and

to appreciate these typefaces.

Comparing Typefaces

In typography, we have to choose an

appropriate type family that respect the message that we want to convey. Good typeface presents the message of the

writer. The Rs display a range of

attitudes, some whimsical, some stately, some mechanical, others calligraphic

some harmonious and some awkward.

The

uppercase letter forms below suggest symmetry.

But in fact, it is not symmetrical.

We can see it that there are two different stroke weights of the

Baskerville stroke form (below); more noteworthy is the fact that each bracket

connecting the serif to the stem has a unique arc.

Picture

below may looks symmetrical, but a close examination shows that the widht of left

stroke is thinner than the right stroke.

The complexity of each individual

letterform is neatly demonstrated by examining the lowercase ‘a’ of two

seemingly similar sans-serif typefaces—Helvetica and Univers. A comparison of how the stems of the

letterforms finish and how the bowls meet at the stems quickly reveals the

palpable difference in character between the two.

Maintaining X-height

The x-height generally describe

the size of the lowercase letterforms.

However, the curved strokes, such as in o, a, s, and r, must be rise

above the median (or sink beyond the baseline) in order to appear to be the

same size as the vertical and horizontal strokes they adjoin.

Counterform

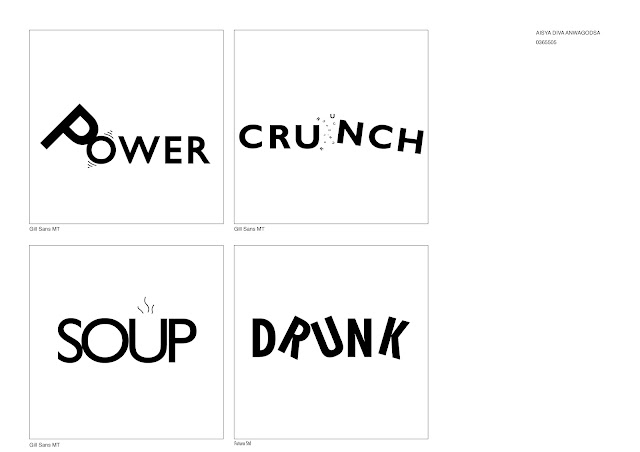

Counterform: Counterform

is the blank spaces between individual letters and as designers this can be

used to significant effect, also referred to as ‘negative space’. By

definition, a word has the potential to express an idea, object, or event.

(https://brucewilsongraphics.wordpress.com/2012/10/17/counter-form/)

The basic principles of Graphic Design apply directly to typography. The following are some examples of contrast—the most powerful dynamic in design—as applied to type , based on a format devised by Rudi Ruegg.

Tell me you like typography without telling me you like typography:

|

| Fig. 2.7 Final outcome process (4/11/2023) |

|

Fig. 3.4 Final Outcome (26/10/2023) |

Font/s: Gill Sans MT

Type Size/s: 48/12

Leading: 24

Paragraph spacing: 12

Font/s: Gill Sans MT

Type Size/s: 10

Leading: 12

Paragraph spacing: 12

Characters per-line: 54-64

Alignment: Left Justified

Columns: 4

Gutter: 10 mm

Font/s: Gill Sans MT

Type Size/s: 33/12

Leading: 24

Paragraph spacing: 24

Font/s: Gill Sans MT

Type Size/s: 10

Leading: 12

Paragraph spacing: 12

Characters per-line: 54-60

Alignment: Left Justified

Columns: 4

Gutter: 8 mm

QUICK LINKS

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment